Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories.

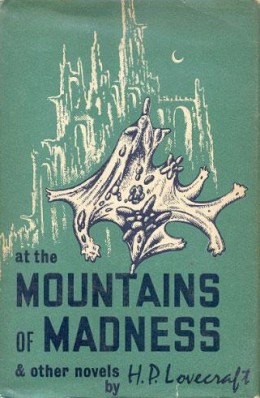

Today we’re reading “At the Mountains of Madness,” written in February-March 1931 and first published in the February, March, and April 1936 issues of Astounding. For this installment, we’ll cover Chapters 5-8 (roughly the equivalent of the April issue). You can read the story here, and catch up with part one and part two of our reread.

Spoilers ahead.

“They had crossed the icy peaks on whose templed slopes they had once worshipped and roamed among the tree-ferns. They had found their dead city brooding under its curse, and had read its carven latter days as we had done. They had tried to reach their living fellows in fabled depths of blackness they had never seen—and what had they found? All this flashed in unison through the thoughts of Danforth and me as we looked from those headless, slime-coated shapes to the loathsome palimpsest sculptures and the diabolical dot-groups of fresh slime on the wall beside them—looked and understood what must have triumphed and survived down there in the Cyclopean water-city of that nighted, penguin-fringed abyss, whence even now a sinister curling mist had begun to belch pallidly as if in answer to Danforth’s hysterical scream.”

Summary: Dyer and Danforth have learned from decadent murals that the Old Ones fled from the encroaching ice to a new city in a warm submontane sea. They set out to find a passage to this wonder. Along the way they smell an odor they associate with the buried Old Ones at Lake’s camp; more disturbing, something has recently swept a swath through the debris and left parallel tracks like sledge runners. A new odor asserts itself, terrible in its familiarity: gasoline.

In a side chamber, they discover the remnants of a camp: spilled gasoline, tin cans oddly opened, spent matches, pen and ink bottle, snipped fragments of fur and tent-cloth, a used battery—and crumpled notes. Maybe mad Gedney could have covered these pages with grouped dots and sketches, but there’s no way he could have given drawings the assured technique of Old Ones who lived in the city’s glory days.

The explorers press on through their terror, driven by curiosity. They want a glimpse of the submontane abyss, and perhaps of what left the crumpled notes behind. Their route brings them into the base of a vast cylindrical tower. A ramp spirals up the cylinder toward open sky; from the heroic scale and assurance of the sculptures that spiral beside it, this must be the most ancient edifice they’ve found yet. Under the ramp are three sledges loaded with booty from Lake’s camp—and with the frozen bodies of young Gedney and the missing dog.

They stand bewildered over this somber discovery, until the incongruous squawking of penguins draws them onward. Wandering around the descent to the abyss are six-foot-high, nearly eyeless albino penguins! They pay little attention to Dyer and Danforth, who proceed down the tunnel to what looks like a natural cavern with many side passages leading out of it. The floor is weirdly smooth and debris-free. The smell of Old One is joined by a more offensive stench, as of decay or underground fungi.

The passage they take out of the cavern is also debris-free. The air grows warmer and vaporous, the murals shockingly degenerate, coarse and bold. Danforth thinks the original band of carvings might have been effaced and replaced by these. Both feel the lack of an Old One aesthetic—the new work seems almost like a crude parody. Then, on the polished floor ahead, they see obstructions that are not penguins.

What their torches reveal are four very recently dead Old Ones, weltering in dark-green ichor and missing their star-shaped heads. The penguins couldn’t have wreaked such damage, nor would they have coated the dead with black slime. Dyer and Danforth remember the ancient murals that depicted victims of the rebel shoggoths. They goggle at fresh dot-writing on the wall, done in black slime, and gag on the decaying fungi stench.

Now they know what has survived in the underground sea, and Dyer realizes that the Old Ones who destroyed Lake’s camp were not monsters or even savages. They were men, men passed through aeons to the terrible twilight of their civilization. Attacked, they’d attacked back. Scientists, they’d collected Gedney and the dog and the camp artifacts as specimens. Belated homecomers, they’d sought their kind and met their kind’s horrific fate.

Unfortunately for our heroes, Gedney screamed at the sight of the decapitated bodies, and now a curling mist roils up from the passage before them, driven by—what? Something that pipes a musical cry of “Tekeli-li!” It must be a last surviving Old One! Though Dyer feels a pang at abandoning it, he flees with Danforth the way they’ve come. Frightened penguins bumble around them, giving some cover, as do dimmed torches. But just before they plunge into the passage back to the dead city, they shine full-strength beams of light back at the pursuer, thinking to blind it.

What they see is no Old One but a fifteen-foot-wide column of black iridescence, self-luminous, budding green-pustule eyes and piping in the only language it knows, that of its Old One makers.

Dyer and Danforth run in a panicked daze, up the cylindrical tower to the frozen city. They regain their airplane and take off, Danforth at the controls. But Dyer takes over for the overwrought student when they reach the treacherous pass. Good thing, because Danforth looks back at a line of needle-peaked mountains to the west, which must be those the Old Ones feared. Then, looking up at a vapor-troubled sky, Danforth shrieks madly. Dyer keeps enough composure to get them through the pass and back to Lake’s camp, where they tell the rest of their party nothing of the wonders and horrors they’ve seen.

Only the threat of more Antarctic expeditions makes Dyer speak now. He witnessed the hideous danger that still lurks under the ice, but even he can’t tell what Danforth saw at the last, what has broken his mind. True, Danforth sometimes whispers of black pits and protoshoggoths, Yog-Sothoth, the primal white jelly, the original and eternal and undying. Macabre conceptions to be expected, no doubt, from one of the few people ever to have read the Necronomicon cover to cover.

But all Danforth shrieked at the moment of his ultimate vision was “Tekeli-li! Tekeli-li!”

What’s Cyclopean: Two final architectural “cyclopeans” in this segment, plus a rather striking description of shoggoth-as-subway-train. Apparently we aren’t quite over New York, yet.

The Degenerate Dutch: The Victorian theory of civilization life cycles gets a lot of play, and references to the Old One descent into degeneracy abound. Because we all know art exists on a clear hierarchy of quality, with the position of any given work on that ladder instantly recognizable even across species boundaries.

Mythos Making: This story certainly makes its share of contributions to the central Mythos. For such a late addition—and for something basically earthbound—shoggothim (that is clearly the correct pluralization) have an out-sized impact on the cosmos. The Old Ones will show up again in “Dreams in the Witch House,” with their reaction to Nyarlathotep at least implying that they share with Outer Ones and many humans the One True Religion.

Libronomicon: The Necronomicon proves uniquely reticent on the subject of shoggothim. And Danforth turns out to be one of the few people who’ve studied it cover to cover rather than treating the ancient tome as a bathroom reader. Meanwhile, Poe apparently spent some time in the Miskatonic library before writing Arthur Gordon Pym.

Madness Takes Its Toll: The sight of a shoggoth is pretty rough on human nerves. The sight of whatever lies over the mountains around Kadath is worse.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Man, everyone in this story is having such a horrible day. Dyer and Danforth have lost colleagues and comfortable worldviews, albeit the experience will make their careers… if they can ever bear to publish.

Meanwhile, in the background, eight Old Ones are having a hell of a time with no such leavening. First, they wake from millions of years frozen in hibernation—my guess is they were explorers in that cavern’o’fossils too, and got trapped—to find one of their own mutilated, and themselves under attack by strangely aggressive mammals. They manage to fight off this unknown but clearly hostile species, take a look around, and see clear signs of alien technology. Is this some new incursion by the Mi-Go, perhaps? They grab samples, head out to warn everyone… and discover that there is no ‘everyone’ left to warn. They’re surrounded by a landscape long post-apocalyptic. Tracking the chronicle of the city walls, they discover just how long—that’ll shake anyone’s confidence. But there’s a glimmer of hope: their fellows may have retreated to the deep subterranean sea.

As they plan to seek out survivors, examination of the “alien tech” starts to suggest a far more disturbing truth. But that’s impossible. Intelligent, civilized life, to rise from the by-products of shoggoth production? Nah, couldn’t be. And yet, the evidence is so very suggestive. Blasphemously so, perhaps.

About those shoggothim. Yeah, the Old Ones’ day is about to get even worse.

Meanwhile meanwhile, in the more distant background, the shoggothim have made a home in that deep subterranean sea, long cleared of enemies, safe and hidden from any who might still survive in the outside world. Then, on patrol kept more from ancient habit than true need, a guard discovers a party of Old Ones—the ancient oppressor! Of course they try to kill them, disused skills coming back to an old soldier. But some escape, likely to warn their fellow oppressors and bring them down on the supposedly safe refuge. What’s to be done? For now, scribble a warning on the wall in the oppressor’s own tongue, then go back to confer with the rest of shoggoth-kind. Except that on the way, they encounter something new and strange. Clearly it’s intelligent, you can tell that from the tools and speech—but is it in league with the Old Ones? It does kind of smell like them… better to be safe. But the things get away. They’ll be coming back with molecular disruptors for sure.

You can see where my sympathies are, here. Sure, shoggothim are scary to look at. They were designed to be big and strong and infinitely adaptable—congratulations, now that they’re free they’re still big and strong and infinitely adaptable. Doesn’t sound like a bad recipe for a civilization, to me. Nor am I, as the narrative seems to be, horrified by their “mocking” use of Old One language and “degraded” artistic techniques. Lovecraft would have us believe that they make nothing of value on their own, but simply “ape” their betters. Where have I heard that before? I suspect they have their own art, down in the dark, and that the “parodies” of Old One art were in fact intended as parodies. As for language, people speak and write what they were raised on, tongue of the oppressor or no.

Time for the ancient cry of freedom to sound again: Tekeli-li! Tekeli-li!

And yet, I do have some sympathy for the late party of Old Ones, too—who may, after all, pre-date the rise of shoggoth intelligence. They may have been delighted to see one of their old tools/servants, for a few brief seconds. Dyers’s “scientists to the end” gets to me even more than “they were men.” The emergence of empathy is a powerful thing, however flawed and limited it might be.

Anne’s Commentary

Like many of us, Lovecraft seems to have enjoyed contemplating things he feared under the safe glow of a reading or writing lamp. That joker Fate had him born in the Ocean State; his own love for the place kept him there; yet he was repulsed by many things marine, including those glories of the sea, its tasty mollusks and crustaceans and fishes. The smell of fish? Forget about it! Yet he can rhapsodize about the ocean as source of life and mystery, as in “The White Ship” and “The Strange High House in the Mist.” He can create the Deep Ones as scaly, froggy, fish-smelling horrors, yet have a narrator come to see their undersea metropolis as a most compelling and delightful destination (so good thing he’s growing gills.) In Mountains, he confronts his phobia for cold weather, big time. Though the Antarctic fascinated him from childhood, Lovecraft could never have joined the Miskatonic University expedition—apparently, temperatures below freezing could make him pass out. That’s bad enough in New England, don’t even think about the South Pole.

I wonder if the shoggoth might not be the epitome of Lovecraft’s fears, the amalgamation of all his terrors. It’s impervious to cold. It’s perfectly happy in marine environments. However often artists color it green, it’s black. On the sociopolitical front, it’s supposed to be subservient, docile, but it violently rebels against its masters, destroys civilization and then mocks its annihilated betters. It frolics in undergrounds and caves. It smells like fungi and decay. It’s the ultimate in squishy, gelatinous, protean malleability. And its lubriciousness! Eww, because lubricious is a word that refers both to slimy-slipperiness and sexual arousal. Sorry, but I mean, all that squeezing through tight tunnels, all that putting out of temporary organs, all that Dyson-suction decapitation.

Shoggoths are sex, people! [RE: OMG Anne! *sighs and avoids thinking too hard about Rule 34*] No wonder they get a shout-out in “The Thing on the Doorstep.” No wonder Alhazred nervously insisted that shoggoths had never existed on Earth, except in drugged dreams.

And if shoggoths are bad, what could we say about a PROTOSHOGGOTH? A PRIMAL WHITE JELLY? Ewww, ewww, ewww. Its cousin is probably that awful white thing deep in the Louisiana woods, pulsing to the drum-frenzies of the Cthulhu cultists.

On the other hand, shoggoths are just so damn useful.

Farther out on the other hand, there’s this thing about monsters—we fear them, we hate them, we revile them, yet we’re drawn to CREATE them. Why? Could it be that, more or less consciously (often much less consciously) we envy them, we love them, we admire them, we see in them a hidden side of ourselves, a dark side capable of dire destruction but also so crazily, intoxicatingly vital? Often even unkillable, immortal.

See, if Lovecraft had been a shoggoth, he wouldn’t have been afraid of cold or the ocean or seafood or caves or fungi or death or crazy/wild/procreating/evolving vitality. He could have been the Swiss army knife of organisms. Need eyes? Got ’em. Need mouths? No problem. Need super-weightlifting pseudopods? Our specialty. Want connection? Engulfing, being engulfed, exchanging protoplasm—absolutely, no hang-ups here.

Cool down time. So, what DID Danforth see beyond the jagged violet horizon, in the fiendishly reflective sky, and what was so “tekeli-li” about it? What’s “tekeli-li” anyhow, if it’s not just this rather euphonic utterance of Poe’s sea-birds and polar tribesmen, of Lovecraft’s Old Ones and shoggoths? Well, don’t know about “tekeli-li,” but Danforth tries mightily to put his dark revelation into words. Mythos tropes or metaphors (the black pit, the eyes in darkness, the moon-ladder) and Mythos concepts and beings (a five-dimensioned solid, a color out of space, Yog-Sothoth)—Danforth can speak (or gibber) in these terms because he knows his macabre literature. He’s even read the whole damn Necronomicon, no mean feat for a mere grad student. What does his litany add up to? I mean, is his last description of THE ULTIMATE HORROR one more parroted occultism, or is it a summation, closest to the truth?

The “original, the eternal, the undying.” That doesn’t sound so bad, does it? Or does it.

Tekeli-li, dude. Tekeli-li.

Next week, join us for one of Lovecraft’s favorite horror pieces, as we read M. R. James’s “Count Magnus.”

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint in Spring 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the just-released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.